The early modern period was not one of gender equality. Gender inequality was a cornerstone of life which extended from the public sphere to family life, where the role of women was markedly different from that of men, on the assumption of female inferiority with regards to most tasks.

Despite this (and largely because of it), early modern texts are often analysed through a feminist lens, which is to say that the role of gender is often seen as a crucial factor in understanding characters, scenes, or even entire plays. This type of criticism is particularly valuable when gender roles are—deliberately or accidentally—subverted (which happens a lot). Increasingly, however, female characters in popular early modern plays are seen as so empowered that the writer simply must have had a ‘proto-feminist’ agenda. There’s certainly no reason this couldn’t be the case but any writing produced at a time where women were de facto and de jure discriminated against requires a large burden of proof if it is to be labelled ‘feminist.’

One theme I’ve noticed is for female characters to be described as feminist icons after having acquired some qualities which empower them but these qualities are explicitly masculine or notably un-feminine. The empowerment is not through an equality of the sexes or embracing a character’s femininity but rather stripping it away (treating it like a weakness which empowers the character once removed). While not a fictional character, Queen Elizabeth I is a prime example of this kind of gendered empowerment which sees empowering women as necessitating a sort of de-feminisation. In 1588, the year of the Spanish Armada, Elizabeth gave a rousing—and famous—speech to the English forces at Tilbury. It was during this speech she uttered these famous words:

I know I have the body but of a weak, feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king

The British Library explains this as ‘Elizabeth defend[ing] her strength as a female leader.’ This is certainly true, as Elizabeth’s capabilities to defend the realm had been questioned on the grounds of her gender, but there’s more to it. In empowering herself as a female ruler, she’s compelled (by the culture of the time) to argue not that her gender is irrelevant, or that it is her femininity which gives her strength, but rather that she is only superficially female and internally has the masculine qualities of a king. It would be unfair to expect her to champion gender equality, of course, but the subtle detail here is the acceptance of misogyny. Elizabeth essentially accepts the sexist premise but in turn uses it to empower herself.

To find fictional examples, look no further than Milton and Webster. In The Duchess of Malfi (1613), the titular Duchess is often seen as a strong female character who is empowered by John Webster. Again, however, many instances of this empowerment actually hinge on the acceptance of misogynistic ideals. In Act 1, Scene 3 there is a poignant moment where the Duchess’ two brothers confront her on her potential decision to remarry and Ferdinand argues ‘Marry! they are most luxurious/Will wed twice’ to which the Duchess retorts ‘Diamonds are of most value,/They say, that have pass’d through most jewellers’ hands.’ This moment is undeniably one in which the Duchess appears resilient, confident, and witty. Nonetheless, it’s interesting to observe that in choosing the analogy she does, the Duchess is accepting one which treats the female as passive (a diamond) and the male as active (the jeweller) whilst also setting a clear power dynamic—one which favours men. There are two reasons this is unsurprising, however. Firstly, the Duchess is simply using the sexist rhetoric employed by her brothers against her and exposing the irrationality of their rules regarding women’s value by following them to their logical conclusion. Secondly, the Duchess isn’t actually saying anything: Webster is. The playwright could hardly be expected to move entirely beyond the sexist bedrock of the time and to expect him to is overly-optimistic. So while the acceptance of some sexist premises is interesting to note, it doesn’t mean that a character can’t be seen as one which challenges contemporary gender roles.

Later on in the first act, the Duchess’ servant, Cariola, wonders ‘Whether the spirit of greatness or of woman/Reign most in her.’ This is a consistent theme of the play and one which readers will at times wonder: is the Duchess’ defiance of her brothers a sign of bravery or of reckless over-confidence? According to Cariola, and by reasonable extension Webster, the question is also one of ‘greatness’ versus ‘the spirit […] of woman.’ If the Duchess is acting bravely and admirably, she must be acting in a way which is explicitly anti-feminine. The ‘spirit of […] woman’ is a reference to Eve in the story of the fall of man, as she is tempted by Satan to disobey God. This line neatly underlines why women were seen as foolish & misguided and also highlights that this was seen as a crux of their nature, not merely a possibility.

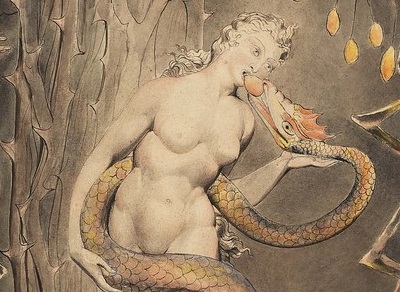

On the topic of Eve, there is a moment in Book 9 of John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667) where a similar question surrounding a character’s portrayal arises, and that character is Eve. There is a moment where Satan, in the form of the serpent, approaches Eve and we’re told that:

‘Her graceful Innocence, her every Aire

Of gesture or lest action overawd

His Malice, and with rapine sweet bereav’d

His fierceness of the fierce intent it brought‘

The effect only lasts a few moments but the point is made: even if only for an instant, Eve’s innocence and (as it’s implied) beauty actually overpowers Satan. In this example, her power stems from traditionally female qualities, but once again the question of whether this is a good ‘feminist’ moment is kind of a tricky one. Yes, Eve isn’t sacrificing her femininity to gain strength, but are these qualities really ones which a feminist author would choose to empower? There is a similar moment in Act 4, Scene 2 of The Duchess of Malfi where the Duchess, facing her own assassination, exclaims that ‘I am Duchess of Malfi still’, embracing her (female) title and standing firm in the face of men who mean her harm. Yet her title is now only superficial and was bestowed on her by virtue of her (now deceased) husband (and from a Feminist-Marxist standpoint, the idea of empowering a female character through asserting her status as a landed noblewoman is problematic to say the least). Similarly, Eve’s beauty and innocence are essentially out of her control and since they’re the only qualities which afford her power but are also fundamental to her seduction (her innocence extends to naivety) and superficial, it’s easy to also argue that Milton is actually engaging in a treatment of gender which, like the Duchess, accepts female passivity.

If we’re talking about early modern literature, I can hardly leave Shakespeare out, so here’s an example from him. In 2019, The Independent writer Olivia Petter compiled Shakespeare’s ‘five most feminist characters’ and one of the contenders is Portia from The Merchant of Venice (c. 1596). One of her examples of Portia’s actions which cements her as a ‘feminist’ character is her clever treatment of the test her father has made her give each suitor, which she manipulates to help her marry who she really loves. The other is what she is most remembered for: disguising herself as a male lawyer (a tautology at the time because women could not become lawyers) and exploiting a loophole to save Antonio, who would otherwise have been killed. This example is particularly interesting because Portia is not simply attributed ‘masculine’ characteristics to empower her, like the Duchess, but is literally forced to disguise herself as a man. Any contemporary theatrical production involving female characters would see them played by men (probably younger boys) anyway, which is interesting in itself from a feminist perspective, but this plot point pressures even modern productions to (superficially) masculinise her character. Again, the fact that a woman is the one to save the day (and the life of a male character) obviously subverts orthodox gender stereotypes but it is a type of ‘feminism’ which is forced to operate within a patriarchal landscape.

Even if the specifics of individual characterisations can be debated, one thing is very clear: the fundamental social order is never challenged. In reading all of these works, you will never find that an equal (or matriarchal) society is being proposed. In fact, the struggle is never even between patriarchy and an egalitarian society; the struggle is between patriarchy and chaos. When the male elites of The Duchess of Malfi are killed in the final scene, the gap is immediately filled by her son, even though Antonio (the Duchess’ husband and her son’s father) desired that he ‘fly the courts of princes’ in the moments before his death. The societies of the play and of their real authors’ is one so grounded in patriarchal gender norms that an alternative structure for society is never even entertained.

None of this is to say that women in early modern literature couldn’t challenge gender norms, often radically, or even act as proto-feminist characters but merely that we have to see any apparently ‘feminist’ messaging as functioning within a context which allowed very little deviance from strict gender norms. When reading literature from this time, it’s worth asking ourselves: is this female character being empowered to challenge gender norms, or does her empowerment rely on the acceptance of those norms in the first place?